Eye For Film >> Movies >> Donkey Skin (1970) Film Review

Donkey Skin

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

Donkey Skin (Peau D'Âne) came out in France in 1970 but had been years in the making in Jacques Demy's head, since he was seven or eight years old and read the 17th century tale by Charles Perrault , which was first published in 1694 in verse. In fact, Demy said he wanted to make the film from the perspective of someone seven or eight years old. That is, of course, only one side of the enchanted coin. He also plays elegantly and adventurously with the conventions of fairy tale films and cinematic storytelling devices and subverts them.

It is impossible to even imagine a Disney version of this tale of a father's incestuous desire and his daughter's escape strategies. And maybe, partly because of that, Demy had fun alluding to some famous Disney moments.

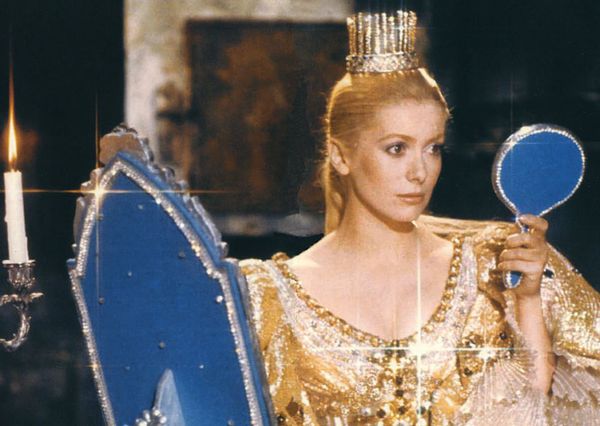

Peau d'Âne's mother, for instance, is put in a glass coffin, that looks like a mix between Snow White's resting place and Cinderella's coach. Both mother and daughter are played by Catherine Deneuve in this, her third collaboration with Demy. When we first meet the Lilac Fairy, played by the marvelous Delphine Seyrig, she is in the woods and switches the colour of her gown, as do the fairies with Aurora's dress in Disney's Sleeping Beauty, while Bambi looks on.

Jean Cocteau and his 1946 version of Beauty And The Beast are referenced on many levels. The king quotes Cocteau as one of the poets from the future. The special effects of reverse motion and slow motion are replicated in all their wonderful simplicity. The caryatids, the living statues, are present as witnesses. The prince is held up by an invisible wall and gets advice from a talking rose. And last but not least, the casting of Jean Marais as the father. Marais, who played both the Beast and what in the later Disney version is known as the Gaston character is the perfect choice for the king.

How do you portray a man, who insists on marrying his own daughter because he promised his wife on her deathbed that he would only re-marry someone more beautiful than she is? How do you tackle the threat? By putting him on a throne in the shape of a gigantic white cat. And by dressing him in the cape of a peacock, in a shape that resembles a bird. Cat and bird at once - which is also the motto of the masked ball in the film.

As much as Demy loves to work with doubles, twins and mirror images - the Demoiselles De Rochefort (Deneuve with her sister Françoise Dorléac) can speak of that - in Donkey Skin seeming contradictions collapse into one. When you think of fairy tale locations, you think of forests and castles. In this case, the forest has invaded the inside of the castle - from the ivy on the walls to the grass bedding. Deneuve, in the famous cake-making sequence is both princess and donkey maid at once. Literally, there is the chicken and the egg. The wise man gives the most stupid advice, the donkey is the banker, the future in the shape of a helicopter lands casually in the past.

Donkey Skin was made in the late Sixties. Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood is his take on a fairy tale set in 1969. Jacques Demy lived in Los Angeles on and off in the Sixties, wrote some of the script of The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg there and shot the film Model Shop with Anouk Aimée. Joan Didion wrote in The White Album that many people "believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969". Donkey Skin is right there at the crossroads, capturing a moment of change as well as the timeless nature of storytelling.

The tale of Donkey Skin is closely related to the tale All Fur, collected by the Brothers Grimm. In both stories, the daughter tries at first to dissuade her father from marrying her by demanding three outrageously complicated dresses. The garments are to resemble the sun and the moon and either shine like the stars, or reflect, in the case of the French version, the weather.

Deneuve commented that the dress was immensely heavy because it was made from the canvas used for movie screens - so that the weather could be projected on it. Objects in tales speak to us in the language of symbols. The princess wants her beauty to be otherworldly, untouchable - to escape the father who asks the King Lear question: "How much do you love me?" She identifies simultaneously with the animal, the filth, a child taking on the guilt of the parent. In her, the above and below human fall together. In All Fur, it isn't absolutely clear if the princess arrives at another kingdom or still is in the same. Demy, by painting the inhabitants of the first kingdom blue and the second one red, gives a nod to that consequential question.

The Lilac Fairy, is according to Donkey Skin producer Mag Bodard, "the most human", this is a fairy godmother therapist with her own agenda and a special connection to the future. Once upon a time relates to the future as much as the past.

Disney movies are so much more comfortable with female villains, and Cinderella, in a way, is Donkey Skin's more famous cousin. The slipper that has to fit, here is a ring. In the Grimms' Cinderella the stepsisters cut off some of their heels and toes - the equivalent to the finger slimming scene. The ashes can hide the truth only for so long.

The songs by Michel Legrand are a perfect example of the genius of his collaboration with Demy. While the melodies enchant us, they tackle subjects such as the incest taboo or they compare love to a "noose around your neck". A parrot nods along, laughing at us humans.

The most unusual musical number has the alter-ego ghosts of the young couple run off together, only to discover that they don't know what to do with each other, with so much love, without obstacles. What they come up with are the most childish pleasures: Eating too much cake, sipping wine and smoking a pipe as the adults do, and rolling down a hill - or up - in their fine clothes. Innocent and spoilt, already bored. The happily ever after is empty, not real, not physical. This perfect love fantasy has already been explored by the same two actors, Deneuve and Jacques Perrin in The Demoiselles De Rochefort, where they represent a disembodied virtual ideal for each other and never even meet.

When I contacted Agnès Varda for a remembrance of Michel Legrand on January 26 of this year, the day the composer died in Paris at the age of 86, she sent the following remark on the playful work atmosphere created by Demy and Legrand. Varda herself, died on March 29, only two months and three days later: "I shared with them that happy time of their lives and their joyful friendship. Our children played together and both of them, in-between their working sessions liked to play with the little electric cars and little trains … Puns and witticisms were launched! Good spirits, melancholy, energy and fantasy were alternating as their inspiration."

The magic of Donkey Skin is that it works for children as well as for adults and that with every new viewing you can discover things you missed before.

Reviewed on: 12 Aug 2019